While perhaps most widely known as the “Acid King” for his early role manufacturing the highest quality LSD to help fuel the psychedelic revolution of the 1960s, he was a self-educated innovator, scientist, artist, and patron of the arts with wide-ranging interests. As such, he had a profound and well-documented influence on other artists, musicians, and sound engineers, among others. (His personal website is maintained at thebear.org)

Owsley essentially recorded every artist that ever played through a sound system that he built.

His catalog is prolific – both in the quantity of recordings and the stature of the artists. These historic recordings comprise what he called “Bear’s Sonic Journals.”

In the creation of his live mixes, or “sonic journals,” Owsley Stanley was unique in his approach to live audio recording. Originally, these sonic journals allowed for a band to critique their performances and for Owsley to refine his recording techniques. Over time, these recordings have become a standard for excellent live stereo recordings.

Owsley used a simple and clean approach, one based on solid scientific principal. He never used equalization (electronic tone control) on individual microphones or on the PA output to correct a poor sound, feeling that such manipulations improperly altered the sound created by the musicians. Instead, if the sound in the hall wasn’t just “right,” he repositioned the microphone or replaced it with a different type of mic until the sound met his standard. As a result, his live sounds were clean, clear, and pure-not electronically corrected. He viewed his role as precisely facilitating the transmission of the music to the audience without altering or manipulating the sound —his goal was to give the musicians complete control over what the audience heard.

Because of the loud volumes intrinsic to a typical rock ’n’ roll stage, microphones pick up much more sound than the engineer may intend, a phenomenon know as “leakage”. For example, a microphone positioned to pick up a snare drum may also pick up a loud guitar amp near it. To help eliminate this effect, engineers typically employ a technique known as “close miking,” where microphones are placed very near to each individual instrument. The end result can be sterile and result in phase shifts, or sound cancellations. Owsley took another approach. While he occasionally used close miking, he also employed something he called “constructive leakage.” By using a minimal number of microphones (he generally used twelve or fewer microphones) and positioning them appropriately, he was able to make use of the leakage in a positive way. This constructive leakage helped create a cleaner and more transparent sound with minimal phase shift problems-a technique particularly useful when recording the very complex instrument of a drum set. Instead of assigning each individual drum to its own microphone, he was able to reproduce a powerful and clear drum sound using only two mics positioned very specifically.

The final stage of signal flow before the tape recorder was the mixer. The twelve microphones needed to be summed to a two-track (stereo) L-R image. Owsley used a very sonically pure mixer, usually several Ampex MX-10s. Simple in design and high in quality, the MX-10 allowed multiple microphones to create a coherent stereo output. The mixer had no pan pots, which degrade the signal, and a microphone was assigned left, center, or right-and here too, none of the mics were equalized; all sounds were pure. The end result was a “picture” of the stage, with the positioning of the instruments spread across the stereo field just as they were heard from the audience’s perspective.

Through the use of high quality equipment, an expert knowledge of acoustics and electronics, and a fine ear for music, Owsley Stanley’s sonic journals captured the essence of live music. To this day, his techniques exemplify the best live to two-track recording.

About The Owsley Stanley Foundation

The Owsley Stanley Foundation is a 501c(3) non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of “Bear’s Sonic Journals,” Owsley’s archive of more than 1,300 live concert soundboard recordings from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, including recordings by Miles Davis, Johnny Cash, The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Fleetwood Mac, Janis Joplin, and more than 80 other artists across nearly every musical idiom. These analog reel-to-reel recordings are nearing the end of their expected shelf lives and will deteriorate and be lost forever if they are not preserved. The effort to preserve these historically vital recordings is estimated to cost between $300,000 – $400,000. All donations and proceeds from the development of the recordings flow back into the effort to preserve more of Bear’s Sonic Journals and perpetuate Owsley’s legacy, including patronage of the arts in all of its forms. Our staff is entirely comprised of volunteers, and many of the support services necessary to run the organization have been donated by generous contributors that believe in the mission to save this music before it is lost forever.

If you want to donate to Owsley Stanley Foundation please click this link: https://owsleystanleyfoundation.org/donations/save-the-music/

Save the Tapes!

The tapes are approaching the end of their known shelf-life, and if the recordings are not digitally preserved, they will be lost forever. Experts believe that the typical lifespan of this media is approximately fifty years if maintained in ideal conditions and have advised the Foundation that the digitization of the earliest of these recordings should occur within the next five years or they will not be salvageable; all of them will continue to degrade and will become unsalvageable unless eventually digitized. The cost of digitally preserving these recordings is estimated to be US $200,000 to US $300,000 and will require two to four years of studio time by sound engineering professionals to complete.

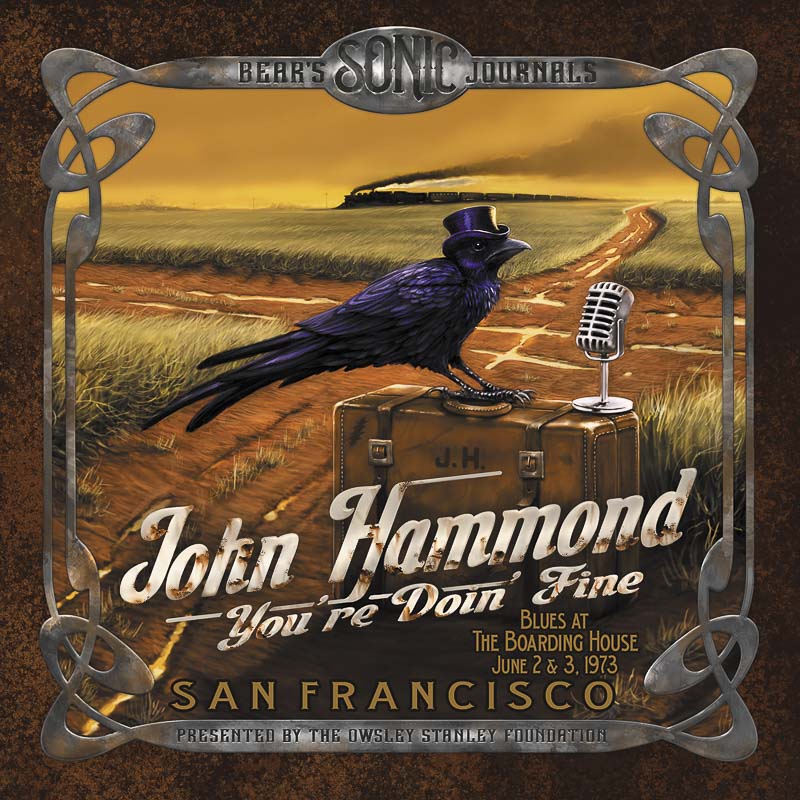

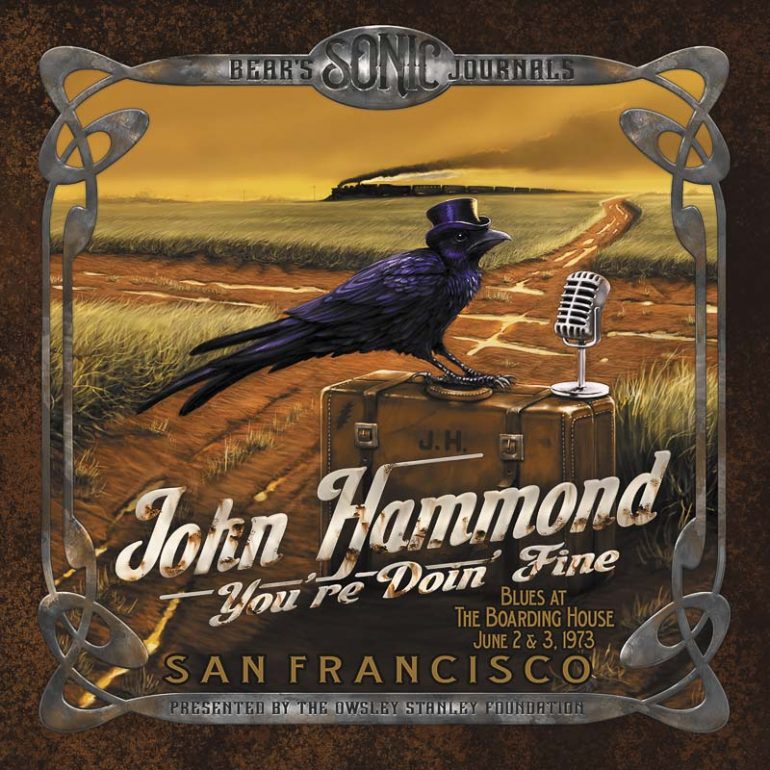

This week on The Flower Power Hour with Ken & MJ, interview with Hawk from the Owsley Stanley Foundation about the release of the John Hammond 3-CD set, “You’re Doin’ Fine – Blues at the Boarding House – June 2 and 3, 1973 San Francisco.”

This week on The Flower Power Hour with Ken & MJ, interview with Hawk from the Owsley Stanley Foundation about the release of the John Hammond 3-CD set, “You’re Doin’ Fine – Blues at the Boarding House – June 2 and 3, 1973 San Francisco.”

Post comments (0)